Search the wiki

01. Principles of Animation

Introduction

The principles of animation were observed in the 1930s onwards by Disney’s leading animators, and were first expounded in The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston in 1981. These principles are worthy of your very close attention, as they provide a beautifully simple set of guidelines that can stand you in no better stead when beginning to animate.

Step 01: Squash and stretch

This principle of animation is based on the fact that all matter in motion retains its volume but does not retain its shape. Consider facial expressions: a smile will stretch the lips and squash the cheeks while a look of surprise will widen the eyes but squash the forehead. You can also use squash and stretch to go from small shapes to large shapes. For example, take the human form jumping: in preparation for the movement, the body squashes down into a crouch before stretching into the leap.

When applied to an animation, these changes in shape through the use of squash and stretch will lend characters fluidity, elasticity, and vitality, and therefore believability. The same rules also apply to material forms, and a bouncing ball demonstrates this very clearly: it stretches as it descends, squashes on impact, and then gradually returns to its original shape as it ascends.

Although you’ll find many examples from cartoons, you should observe the same principle in real-world examples.

Step 02: Anticipation

To allow an audience to understand and engage fully with an animation, we need to give them a certain amount of information to be able to anticipate what is to come. Many a gag is built on creating an expectation of what is to come, and then turning that expectation on its head.

As with squash and stretch, this principle is grounded in physical law: very few movements are not preceded by preparation, which here we call anticipation. Take the following as an example: before standing up, the head and upper body move downwards and the hands grip the side or arms of the chair. Before kicking a ball, the leg is first pulled behind the body, to then come forwards and make contact with the ball.

It’s clear from these examples that the anticipatory action, which often moves in the opposite direction to the main action, serves to generate energy to power the action to come.

Step 03: “Follow through” and “overlapping action”

These terms concern techniques which evolved in order to avoid movement coming to too abrupt a stop. If actions stop dead, then the scene literally dies and the illusion is broken.

Therefore, to soften the stops, animation needs to pay attention to the fact that some parts of the body will become stationary after movement more quickly than others, depending on their mass and on the nature of the action taking place.

In many cases, the pelvis will lead the movement, and the rest of the body will follow behind, and of course, clothes and hair will invariably come to a stop last. For example: as we walk and our arms swing, while the upper arm has already begun to move backwards, the forearm can still be swinging forwards.

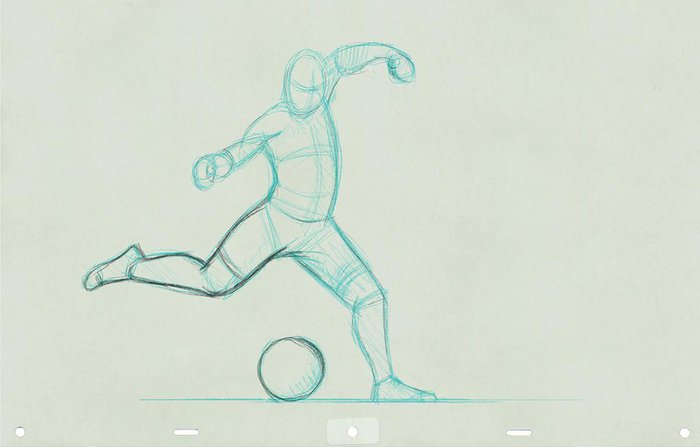

Step 04: Timing

This principle concerns the time in frames that a movement will last for. The exact same movement played slowly or quickly (or somewhere in between) will give an audience very different information. Take the example of a woman running her hands through her hair. Played quickly, the action will transmit to the audience the sense that she is anxious or harried. Played slowly, on the other hand, the same action may give an impression of thoughtfulness or exhaustion.

Timing is also linked to the principles of overlapping and follow through as outlined previously, where we discussed that an action will come to a stop gradually, with some parts of the body returning to a stationary position faster than others.

Step 05: “Slow in and slow out”

In an animated piece, attention needs to be drawn towards the key poses, or those poses which actually tell the story, so that an audience can follow the narrative unfolding in front of them.

For this reason, the in-between poses that create the transition from one key pose to the next, are mainly clustered around those key poses, and there is a breakdown pose at the halfway point between each key pose. Such an arrangement serves to draw the eye toward the key poses while also adhering to natural rhythm, in the sense that we move into and out of positions through gradual acceleration and deceleration.

Step 06: Arcs

Most movement in nature, unless it is very short, travels in an arc rather than a straight line. For example, when you are reading a book, take your hand from the page and touch your nose. Unless you are holding the book no more than a few inches from your face, your hand will trace an arc in the air. When animating, an absence of arcs will result in very stiff, abrupt, and unnatural movement.

Step 07: Secondary action

A secondary action is one which is added to a main action with the intention of supporting and strengthening the narrative or mood of a piece. Picture a scene where two characters are talking (main action). One character gesticulates strongly while talking (secondary action) while the other responds but takes surreptitious glances at the clock behind the other’s head (secondary action). These secondary actions clearly provide additional character information for the audience.

Step 08: Staging

This principle concerns the necessity of presenting concepts in such a way that there is no ambiguity for the audience. A character must be posed in a recognizable way and positioned, with respect to the camera, with perfect visibility. Even the subtlest facial expressions must be staged correctly for the audience to follow the narrative.

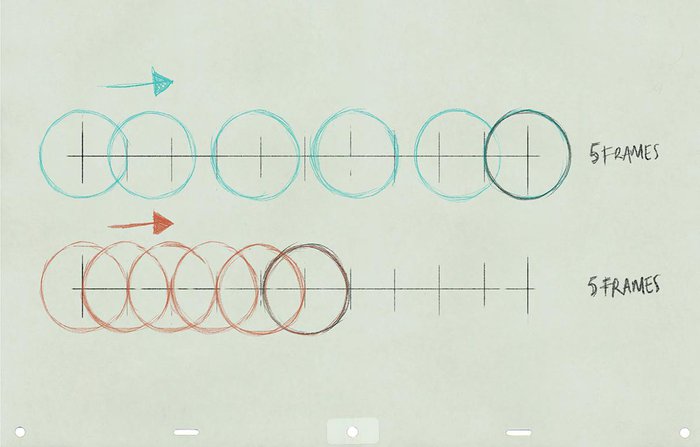

Step 09: “Straight ahead action” and “pose to pose”

These are two methods of animating a piece. In “straight ahead action” the animator starts animating from the beginning of the piece and works through to the end, knowing the premise but not exactly where the journey will take him, just as you might write a story. It is a very spontaneous, organic way of working that can produce some very innovative results.

“Pose to pose”, in contrast, means that the animator will block out all the principal poses of the piece, and the intervening action will be filled in afterwards. Though there is clearly an absence of spontaneity here, there is opportunity for very strong, very readable poses.

Step 10: Exaggeration

Exaggeration is the idea that animation, though it may try to mimic reality, is not reality, and requires an extra push to achieve believability.

A realistic walk cycle, for example, will need a bit more weight going down with each step, and a little more lift with each rise than you’d normally expect to see on the street, in order for it to look “correct” on screen.

Expressions or movements which are too subtle may be lost entirely. When aiming for a realistic look, exaggeration will be slight; when aiming for a cartoony feel, the forms can really be pushed for great comedic effect.

Step 11: Appeal

Appeal essentially relates to anything that an audience takes pleasure in seeing.

Though it may be said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, we are all naturally drawn to good, simple designs, and to ideas that are communicated in an unambiguous way.

Appealing work means that a relationship is formed with the audience, and the audience, therefore, continues to watch.

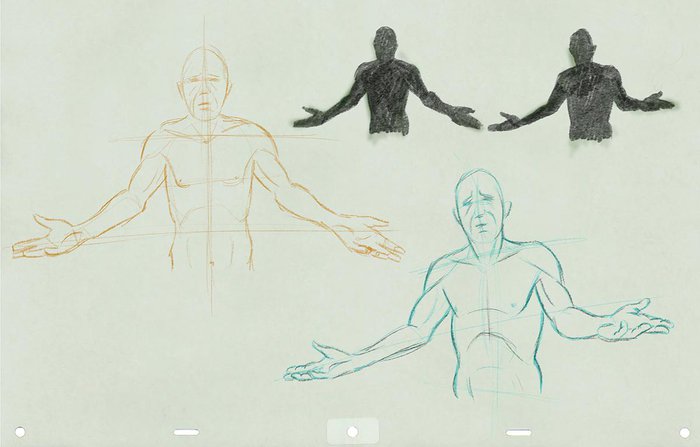

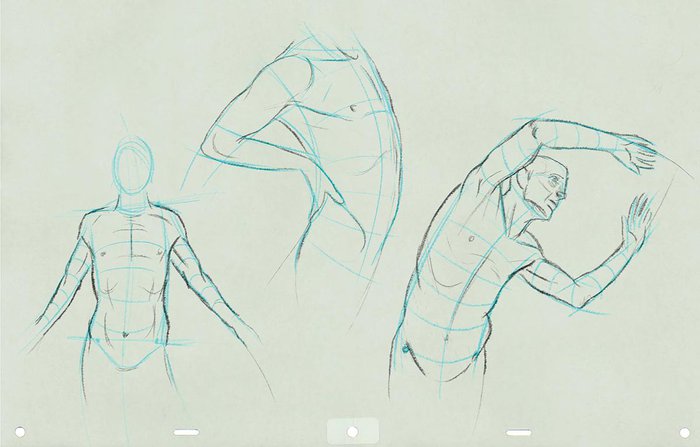

Step 12: Solid drawing

When working away, we recommend an emphasis on the need to understand real-world examples before trying to recreate their counterparts in CG. This principle similarly insists on having strong foundations – here in traditional artistry – before trying to animate.

An artist needs to lend his or her art a real believability in order for it to work, whether on paper or on screen. Your characters should have structure, anatomy, and you should maintain this structure as you animate and deform your characters and objects.

Further Reading

- Disney Archives – The Walt Disney Archives was established in 1970 to collect, preserve and make available for research the historical materials relating to Walt and the company he founded.

- The Illusion of Life – The most complete book on the subject ever written, this is the fascinating inside story by two long-term Disney animators of the gradual perfecting of a relatively young and particularly American art from, which no other move studio has ever been able to equal.

- The Animation Survival Kit – In this book, based on his sold-out Animation Masterclass in the United States and across Europe, Williams provides the underlying principles of animation that very animator – from beginner to expert, classic animator to computer animation whiz – needs.

Support CAVE Academy

Here at CAVE Academy the beauty of giving and sharing is very close to our hearts. With that spirit, we gladly provide Masterclasses, Dailies, the Wiki, and many high-quality assets free of charge. To enable the team to create and release more free content, you can support us here: Support CAVE Academy